Language and history from below

Friday 24 April 2015

Vrije Universiteit Brussel (D.3.12)

The Vrije Universiteit Brussel will host two master classes on historical and linguistic perspectives ‘from below’. These interactive seminars will be taught by Martyn Lyons, Emeritus Professor of History & European Studies and a leading expert on the writing culture of ordinary people, and Stephan Elspaß, University Professor for Germanic Linguistics and a leading expert on language history from below.

These master classes are mainly aimed at PhD students and other early-career researchers, but anyone interested in approaches from below is more than welcome. Students will be sent some preparatory reading beforehand, and will be expected to actively participate during the seminar with questions and discussion where possible.

Schedule

13:30-15:00

Martyn Lyons (University of New South Wales, Australia):

master class on historical perspectives from below

15:30-17:00

Stephan Elspaß (Universität Salzburg, Austria):

master class on linguistic perspectives from below

Venue

Vrije Universiteit Brussel – room D.3.12

(see ‘Practical information‘)

Registration

Participation is free, but participants need to register here by Wednesday 15 April 2015. Attention: the maximum number of participants is limited, so we urge you to register as soon as possible.

Abstracts

Ordinary writings of war and emigration.

Sources and problems for a new history from below

Martyn Lyons

(University of New South Wales)

The ‘Old History From Below’ was dominated by two influential historiographical schools: the French Annales school, and the British Marxists. Both tended to view the subordinate classes in collective and anonymous terms, analyzing collective activism, or collective mentalities. The ‘New History from Below’ is distinctive because it is based on writings from the grassroots, and because it focuses on individual experiences of historical change. We can locate the voices of the forgotten and uneducated by analysing the explosion of lower-class writings brought about by mass emigration from Europe and by the First World War. As a result of these events, ordinary people started to write, in order to re-assert their individuality in a changing and unstable world. Theirs was a writing of absence and desire – the desire to return to one’s loved ones, to familiar surroundings and to the stable co-ordinates of a world which was irretrievably disappearing.

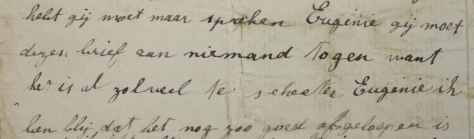

This inter-active seminar will review some of the various genres produced in the remarkable outpouring of popular writing in Europe between about 1860 and 1920, focussing mainly on correspondence. A few problems in studying the ‘New History from Below’ will be addressed: What should we call lower-class writing? – ordinary writings? vernacular writing? ego-documents? And does it matter? Is there a problem of the ‘representativity’ of the texts we are analysing? What allowance should be made (in the First World War armies) for the influence of censorship? Exactly how private was ‘intimate writing’ in the 19th century? What was the role of oral speech in their writing, and does the use of language by semi-literate authors indicate the strength or weakness of national consciousness?

Writing will be approached as a cultural practice; in other words, the cultural historian is interested not so much in the content of correspondence, as in those who sent and received letters, their literary competence, and the function and purpose of writing itself in specific historical contexts.

Private letters by ‘common people’.

A source for a Language History from Below ‒ and for features

of Non-standard average European?

Stephan Elspaß

(Universität Salzburg)

‘Language History from Below’ developed in the early 2000s, following a general surge of interest in alternative language stories. Traditional histories of modern standard languages had primarily focused on national languages and standardization processes. In portraying the modern period, in particular, the narratives of most such traditional language histories comprise printed language, composed and proof-read by a (small) elite of (mostly male) writers, from relatively few (selected) text types and (mostly formal) registers only. Like in ‘histories from above’, ‘language histories from above’ thus present only a fragmented picture of the past, essentially from a bird’s eye view.

Thus, a ‘language history from below’ approach has started from questions that were not addressed – usually not even brought up – in traditional language historiography, such as:

- Who counts as a speaker/writer in language historiography?

- Which texts are used in language historiography?

These questions raised issues like:

- Which speakers/writers have been neglected so far?

- Which texts have been neglected or even ignored so far?

- What would our language histories look like if we took such speakers/writers and such texts seriously and complimented our textbooks with chapters on the language use of lower and lower middle classes and/or on letter writing?

Such questions were encouraged by the adoption of pragmatic and sociolinguistic theory to the study of historical linguistics in the last thirty years or so. The ‘Language History from Below’ approach, however, does not only adopt socio-pragmatic methods in the study of historical texts, but tries to take them a step further. Ultimately, it calls for a radically different perspective in how we see and analyse language histories in historical linguistics. ‘From below’ entails basically two aspects. Firstly, a ‘Language History from Below’ aims at a long overdue emancipation of the vast majority of the population in language historiography, which is represented by the ‘common people’. More importantly, the concept of ‘from below’ pleads for a shift of perspectives to texts from the private spheres and to hand-written material and thus demands an acknowledgment of informal language registers which are fundamental to human interaction. Further questions which arise from this shift of perspectives are:

- What would textbooks look like if we took, say, informal texts by members of the majority of the population as a starting point of the (hi)story of modern languages (i.e. by taking a grassroots approach – or adopting a worm’s eye view, so to speak)?

- What would historical grammars look like if we considered the grammatical forms used in such texts as unmarked default forms (used by a majority of speakers) and grammatical forms in printed texts as marked forms?

- And finally: Which consequences would such ‘alternative’ histories and grammars have on the typological description and classification of ‘Standard Average European’ languages (like German, English or Dutch)?

In this interactive seminar, such questions will be addressed. Most of the illustrative examples will be taken from the language history of German, but there are no German language skills required to follow the presentation and discussion of the examples.

Recommended reading:

Elspaß, S. (2012). The use of private letters and diaries in sociolinguistic investigation. In J. M. Hernandez Campoy & J. C. Conde Silverstre (Eds.), The handbook of historical sociolinguistics (pp. 156–169). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sponsors

These master classes are made possible by the generous support of the Doctoral School of Human Sciences of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel.